Even at the gritty fringes of Oaxaca Centro, the vibe was luminous and seductive, in the very air as we stepped from the hotel’s black gate, our day begun. It felt exotic for us, even with the pavement under our feet wrinkled and broken, one-way traffic pounding the cobblestones in sporadic waves. People live here. The district was beginning to hum with quotidian bustle. Sane and orderly if you’ve also walked Mexican streets in neighborhoods unconcerned about tourism.

Not to be cynical; everyone benefits. In any colonial district made gentle for out-of-towners, you’ll find shopkeepers backlit by the sunrise, sweeping the walkway in front, scrubbing the concrete with soapy water; something I‘ve never seen in Canada. Pride of place. Morning ritual and routine. Wishing a fresh start on the day, some predictability against whatever happens later.

Bringing myself back to Circumspectral, I’ve been reading travel writers and, for more perspective on how this job is done, scouring related reviews and articles. There’s clearly a tension in the genre between tourism and travelling, both in definition and practice, where unscheduled authenticity is much prized above the over-shared attractions of holiday meccas.

As a photographer, I too have been more traveller than tourist out on my picture-seeking journeys these last twenty years. I knew I’d find better material to work with in an unsung town far from the well-worn routes, some isolated dot on the map where the sudden appearance of an unassuming Canadian returns the same curiosity among locals I’m extending their way.

Yet here we were playing that predictable game. We had all of three days. Not a time to cast judgments. It just made sense to embrace the creature comforts close at hand. It could be argued there’s no better place to do it than Oaxaca’s Centro Historico.

The following isn’t so much a story as a series of reports not necessarily in order. Something else, perhaps, differentiating travel from tourism. Travel is chronological. Tourism doesn’t need to be.

Oaxaca Oaxaca

Slower Than Time • Chapter 3

Oaxaca Centro: An Illustrated Tour

We were tourists now, with daybreak optimism, no more ambitious than that. Happy for three days joining aimless throngs milling about Centro, searching our phones for amenities and advice. The essentials: coffee shops, restaurants, parks, museums, tours. In rookie mode, knowing our selections could be hit or miss, even the ones with good reviews. But we felt good about the odds.

We walked under the dapple of sunlit blossoms on the seven-block stroll, three north, four west. The buildings and curbstones were not always parallel, the sidewalk narrowing at times to shoulder-width, often further blocked by inconvenient utility poles, so one needed to cross over. Then on the other side it might be a tree blocking the way, its root system dislodging slabs of pavement. These pathways weren’t made for an open stride, thoughts unburdened by tripping hazards. Whether you mosy, meander, saunter or sashay, watch your step.

That was fine. We are picture takers. Loping ahead in fits and starts, spinning for details, recording the frontage patina, peeling paint intensified by golden hour glow, stepping into the road when traffic allowed for angles and framing. The fabled Zócalo was a natural magnet pulling us inward. An irregular quadrangle of fountains, shade trees and desert horticulture, dominated by a massive church, built by peons to the glory of a foreign god, surrounded by the colonnaded arcades and patio restaurants typical of the country’s colonial legacy.

Like most other mornings, one would guess, the great park was peaceful, waking slowly, gathering its cast of characters: shoe polishers pulling canvas from army green thrones; the frond-broom swish of sweep ladies in safety orange coveralls; a community of vendors trading familiar shouts, unshuttering booths and rigging tarps along the shady edges; a reverent gathering in the cathedral’s shadow; office workers carving brisk shortcuts, indignant pigeons spinning underfoot.

And scattered about, claiming benches, those like us, with no clear purpose, pausing for moments of tranquilidad. Pictures to snap and plans to make, or just to turn the time switch to off and simply observe.

Consider this passage from Viva Mexico! by Charles Macomb Flandrau (1908):

“…even a person of unlimited leisure would have to be doddering, or an invalid or a tramp, before he would consent to sit daily for two or three hours on a bench in a public square, or lean over a balcony watching the same people pursue their ordinary vocations in the street below. In Mexico, however, complete idleness is rarely a bore.

This, I flatter myself, was not on my part a moral obtuseness, but an innate quality of the general Mexican scene. For it is always pictorial and always dramatic; it is not only invariably a painting, but the kind of painting that tells a story.”

From the central plaza, we would first find our coffee fix, some place serving strong with local beans, and absorb the cerebral verve that permeates the zone, countering the mercantile whimsy of souvenir stands and craft boutiques.

Then we’d be free to explore.

North of the Zócalo up towards the Santo Domingo church is the prime activity area for visitors. Over a few hours one can conduct a self-guided circle tour, hopping between a half dozen museums, each unique and worth the time. I tell myself I’m not a museum guy, but my friend is slowly correcting me of my dismissive ways.

Above: Museo de Arte Prehispánico de México (MAPRT)

In 1974, celebrated Mexican artist Rufino Tamayo created Museo de Arte Prehispánico de México (MAPRT), with more than a thousand pieces from the civilizations that flourished in this ancient valley. The museum is not historic in a strictly anthropological sense; it is an art museum, a collection of many works produced by the valley’s ancestors, anonymous artists from different cultures at different times, pouring out their talent and spirituality.

Keep going. There’s a photographic institute honoring the name of Manuel Alvarez Bravo, a pioneer from the early twentieth century. Across the street from the Zócalo is Museo de los Pintores Oaxaqueños, a series of galleries full of modern paintings surrounding a courtyard. We also stopped in at a jewelry salon, a handicraft market and a textile museum, where classes are given.

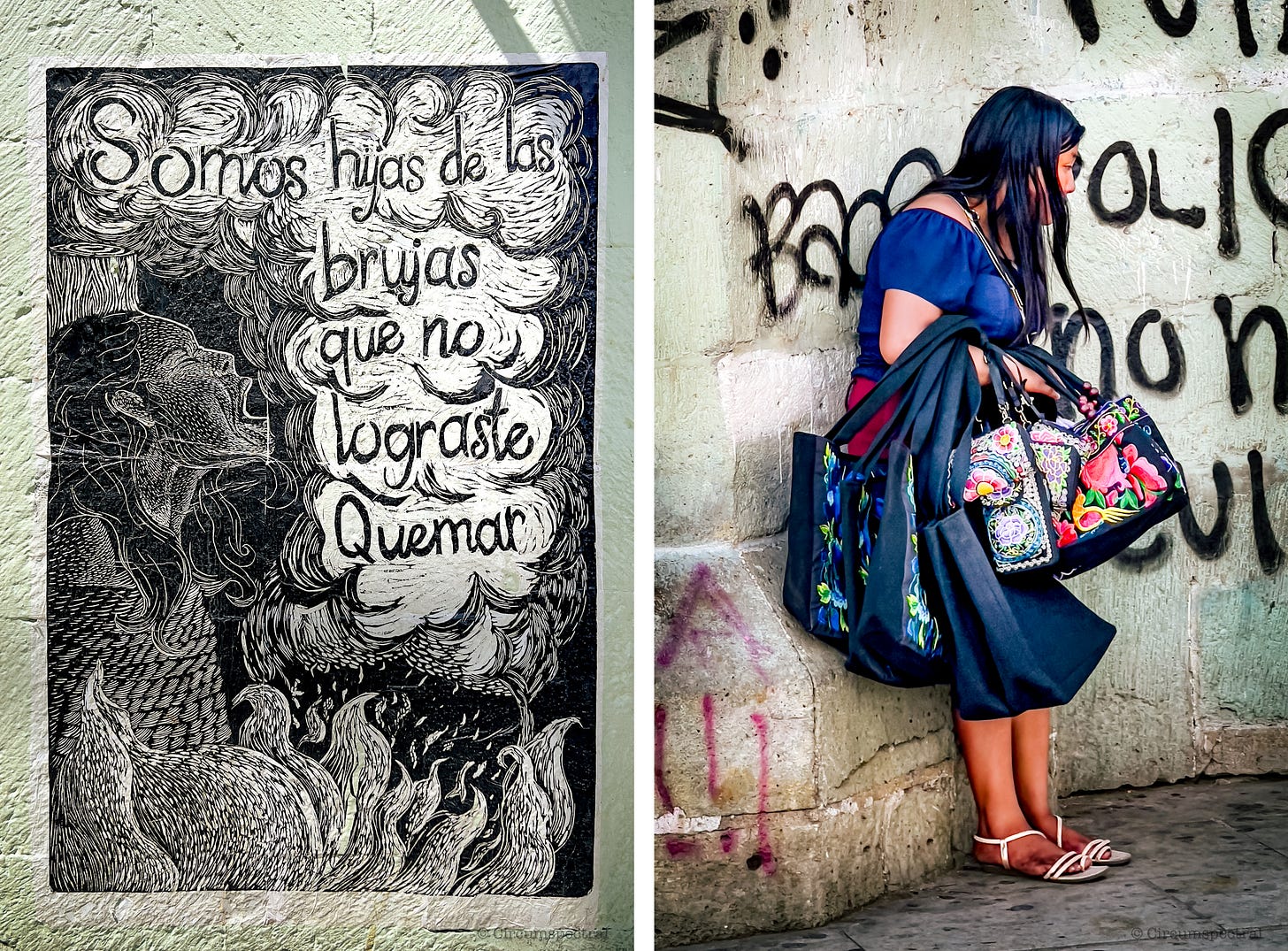

You could even say the whole district is an exhibition space. Behold the riot of creativity adorning every wall.

Left: a transparent sheet of woodcut design pasted flat against the masonry. Translation “We are daughters of the witches you failed to burn.”

Right: A local vendor selling artisanal handbags stands against the ubiquitous pale green stone quarried from hills in the region,

The perceptive observer will sense an undercurrent of rebellion and unrest in these unsanctioned displays. A vivid freeform montage of posters, murals and crude graffiti wherever you walk, signalling ideological unease, not always kind to tourists despite the generally welcoming vibe, perhaps sharpened by inevitable interactions with entitled gringos who don’t always know what they don’t know.

I suppose the ultimate tourist cliché is to climb aboard a double-decker open-air bus. I felt a bit silly, like all I needed was white knee socks and a Tilley hat to complete the picture. But you get the advantage of being above traffic, up where the roof dogs are, and longer views of the mountains beyond.

The tout on the street gave us the low down:

“It’s in Spanish, ok? We leave in 12 minutes. Go down to that blue building, you can buy a beer for the ride. No problem.”

So I did. A Victoria for me. Agua for my friend. We didn’t have an opener; I had to slam the cap against a metal rail, a tricky combination of force and finesse to prevent breakage.

Twelve minutes turned into forty by the time we left. Sad because the warm sunset glow had faded to dusk as we began to move. A twisty tour through Oaxaca’s colonial history, my friend translating. At some point we passed an arena staging a big wrestling event. Lucha Libre. I felt an urge to jump off and join the crowd going in to watch the masked combatants.

Even the less ornamental areas at the rough margins of old Oaxaca offer photogenic splendour. A hundred worthy details popping up whatever the aspect ratio on your preferred recording device, whether phone or camera.

South of the Zócalo is where the merchandisers are. Conducting trade for other Oaxacans. Visitors are gravy. Shirtsleeved urban paisanos bouncing dollies past doorways. Cloth covered card tables laden with trinkets, salsa bottles, tree nuts or bracelets, tended by patient ladies. Two big markets are here, the main one named after Benito Juarez, purveying anything and everything as you navigate a labyrinth of crowded aisles. Mercado 20 Noviembre with its Smoke Hall is in the next block where deli-style meats are flavoured and cured, then laid out on diagonal sheets, stall after identical stall.

Above: The Smoke Hall before and after.

On the left from a visit in 2009: this was once a harrowing hazy warren of eerie passages. Corridors of greasy toxic fumes, thin slices of flesh sizzling and sweating on open charcoal fires, tended by the sisters of the smoke, foreheads glowing in the heat, a smiling sorority helping to quell any dystopian fears. Now made safe, as you can see in the right-hand photo, geometric columns of purifying HVAC, about as threatening as a supermarket deli counter.

And so it went in aimless fascination, everything in proximity. The usual specialty shops selling artisan craftwork and souvenir memorabilia. Chocolatiers selling fragrant chunks by the gram in paper bags. Mezcal emporiums shelved with fanciful bottles of the potent smoky beverage. Humble bookshops, majestic once inside, daunting and learned as any public library. Be alert. If you’re willing to stick your head in dark doorways, you’ll find so much more, especially at the district’s edges, modest little stores selling specialty items, unexpected and surprising

I’m leaving out fine cuisine in this report. I don’t have the foodie gene nor the expertise to expound on local ingredients and traditions with any authority. But it’s there and easy to find; a town famous for excellence and originality. Grasshoppers, for example. We opted for simple, fresh and affordable, preferably in a casual room without a lot of obsequious fuss. Nine times out of ten, my friend orders a salad, with or without chicken. Even by those humble standards, Oaxaca doesn’t disappoint. We did well all four evenings. Morning huevos were top-notch. There’s fresh fruit everywhere. And, of course, try the mezcal! (The two photos above are courtesy of my dear friend.)

Further afield, if you’re in a beatnik mood, head east a few blocks from the big park El Llano and discover hipster-friendly Barrio Jalatlaco. Crudely paved irregular streets resembling a remote mountain village, but only if it was set upon by a squad of energetic artists determined to leave their mark on every vertical surface.

Thus concludes my report of our three days spent as unapologetic tourists in this magical place. We didn’t visit the big archaeological sites, but future postings of Circumspectral devoted to these icons of Zapotec culture are being planned as we speak now that I’m back living here for the next year or so.

We did however travel a few kilometres east to look at a big tree, the subject of the next and final chapter of Oaxaca Oaxaca.

(End of Chapter Three)

Next: Chapter Four, The Tree Of Life.

*This is a personal project, not a business venture, but please consider entering your name in the subscriber box. Writers love a sense of validation.

Always free of charge.